‘Price is what you pay. Value is what you get’

‘Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful’

Warren Buffet

More than €615bn (transactions with disclosed values) were spent on 1780 M&A transactions over the last decade by the 55 world largest FMCG companies. Most of those transactions failed to deliver ROI. Worse, the companies that spent the most on M&A destroyed the most shareholder value. Why?

We reviewed all those 1780 transactions leveraging PitchBook database. We crossed that data with the 2012-22 Euromonitor sell-out data by brand/ countries (>100k+ combinations) and the last 10 years financial reports of the world largest FMCG companies. We then asked ourselves the following questions:

If there is no universal truth and our approach has some limitations (~30% of transactions have undisclosed value for example, some acquired brands are still too small in 2022 to appear on Euromonitor tracking), clear learnings emerge.

Here is our perspective:

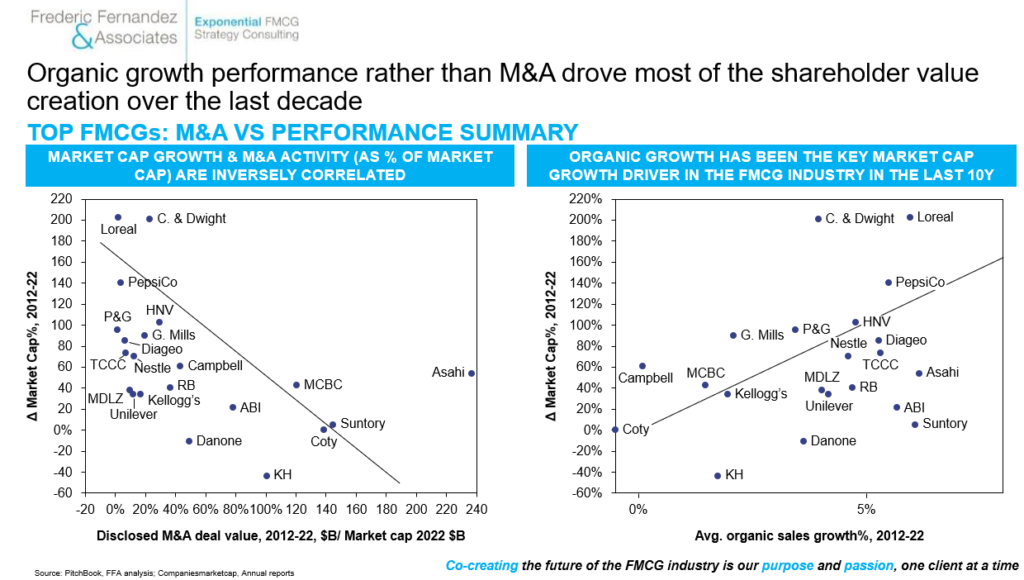

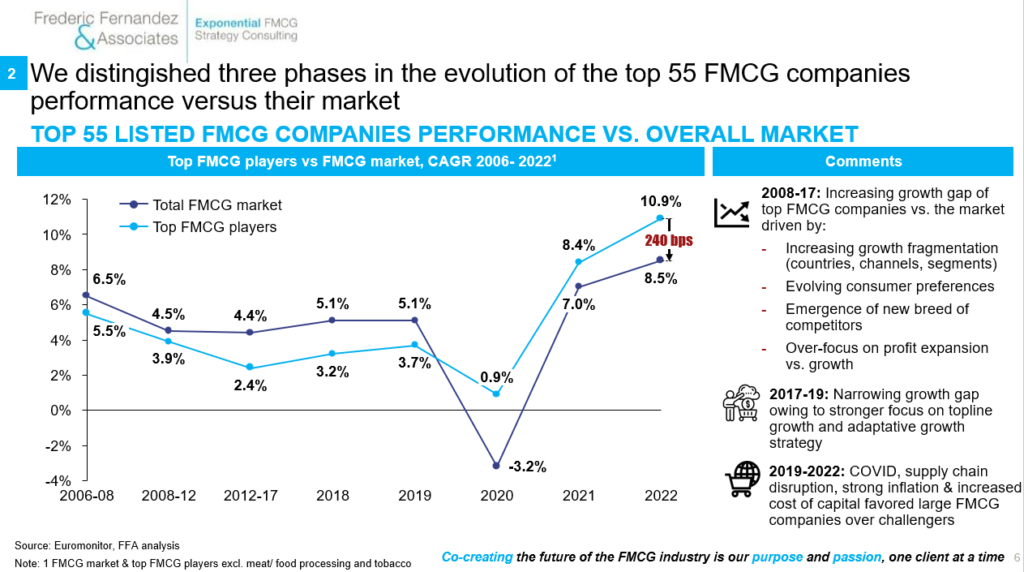

1) Organic growth performance, and not M&A, has been the key driver for shareholder value creation over the last decade in the FMCG industry. Companies that prioritized organic growth while engaging into frequent mid-size (€0.5-6bn) M&A transactions (L’Oreal, Church & Dwight, PepsiCo, Heineken…) outperformed their peers, especially the ones that pursued the largest transactions (>€10bn: ABI, Kraft-Heinz, Danone, Coty…) that ended up performing the worst

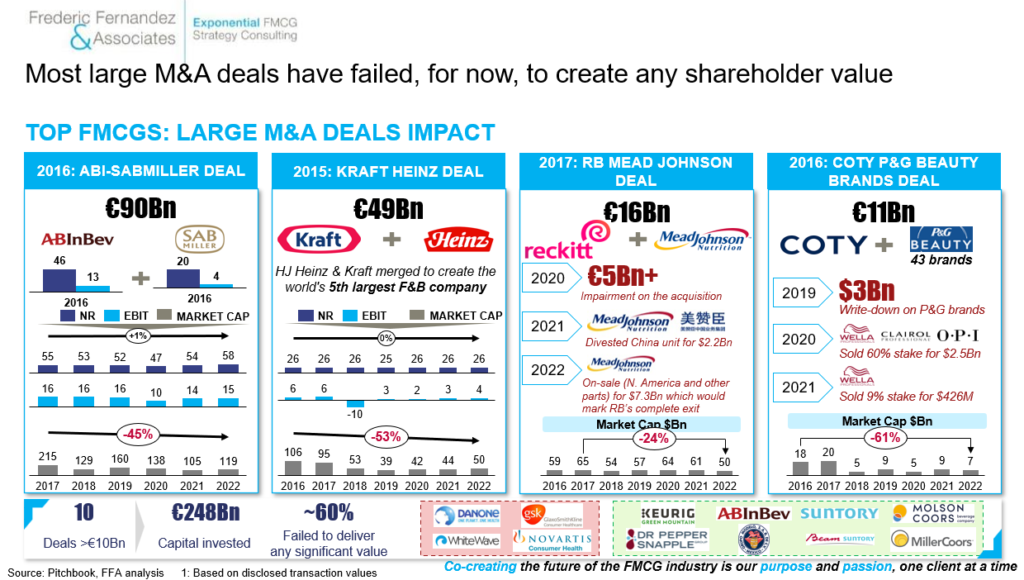

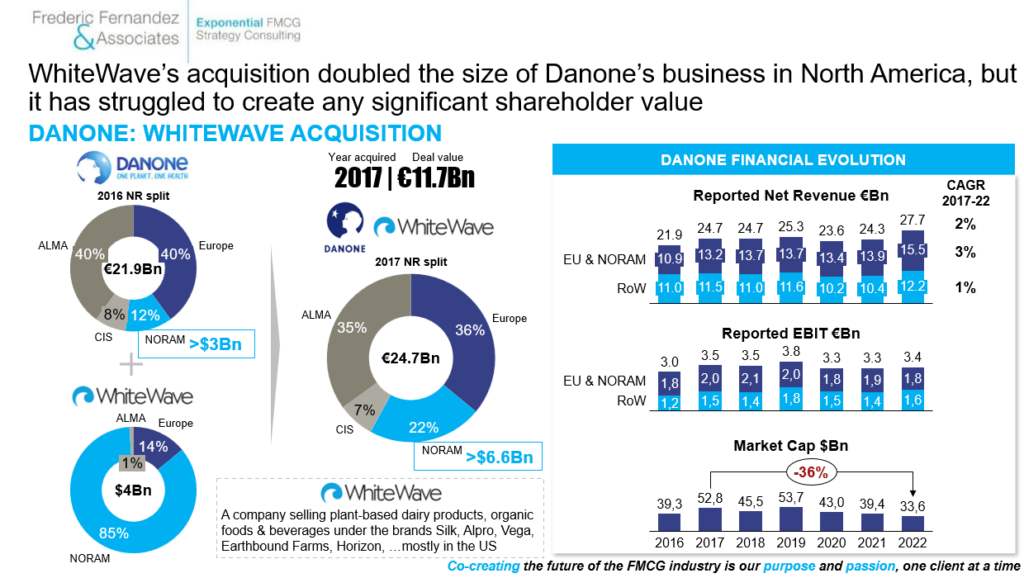

2) Most large deals have, for now, failed to deliver shareholder value. Far the contrary

Few thoughts:

i) If in 10 years, Danone outperforms thanks to its edge on plant-based, will the WW deal be quoted as a ‘decisive accelerator’?

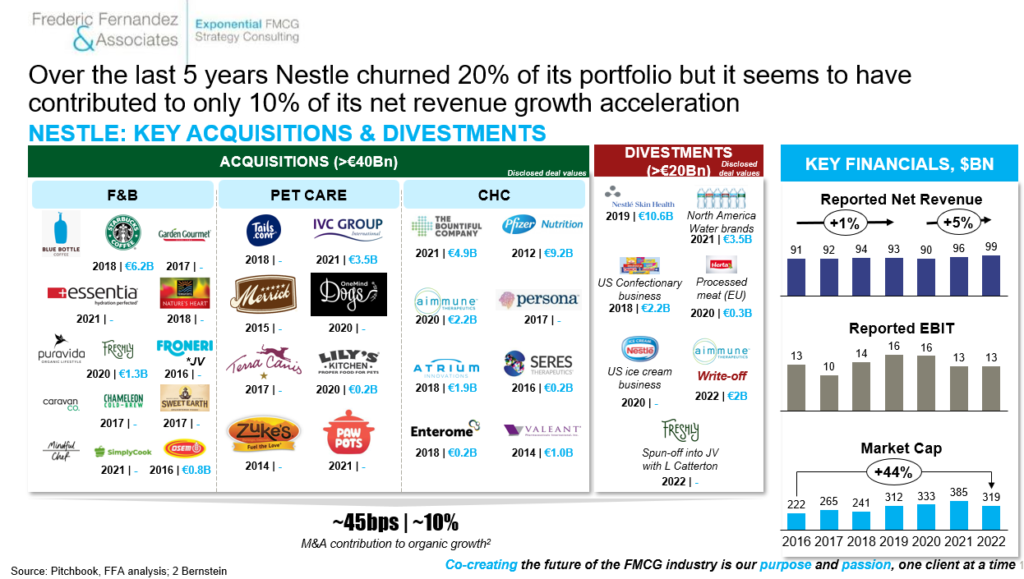

ii) For ABI, what would have been the cost & the time required to build similar positions as SAB-Miller in Africa, especially after risk-adjustment? Anyone that understand the capital intensity behind beer brewing & distribution and the upfront investments required to build a brand in a highly fragmented retail & media environment know that it is a very hard thing to do. Then, look at the demongraphic potential of Africa over the next 50 years. Finally, what if in 10 years BEES (the ABI EB2B platform) ends up being a $100bn market cap listed stand-alone entity and that 50% of its value is driven by Africa? Will we call this then a genius move?

i) First, the focus was maybe too much on the Target’s profitability improvement vs. topline growth acceleration

ii) Second, the acquirers did not have necessarily enough organizational bandwidth to execute a seamless integration without impacting the acquirers’ base business

iii) Third, financial markets expectations could have been better managed through highlighting better the huge complexity behind such integrations, the cost of building vs. acquiring and the associated long-term benefits/ optionalities

We have to recognize that in hindsight, it is always easier to comment. The French dramatist Destouches used to write ‘Criticism is easy, and art is difficult’. Indeed

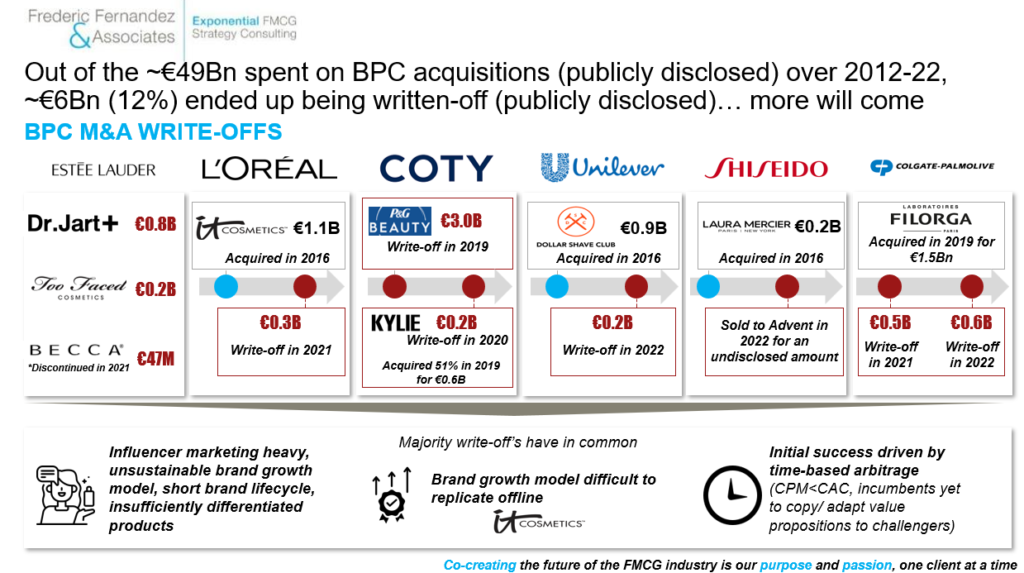

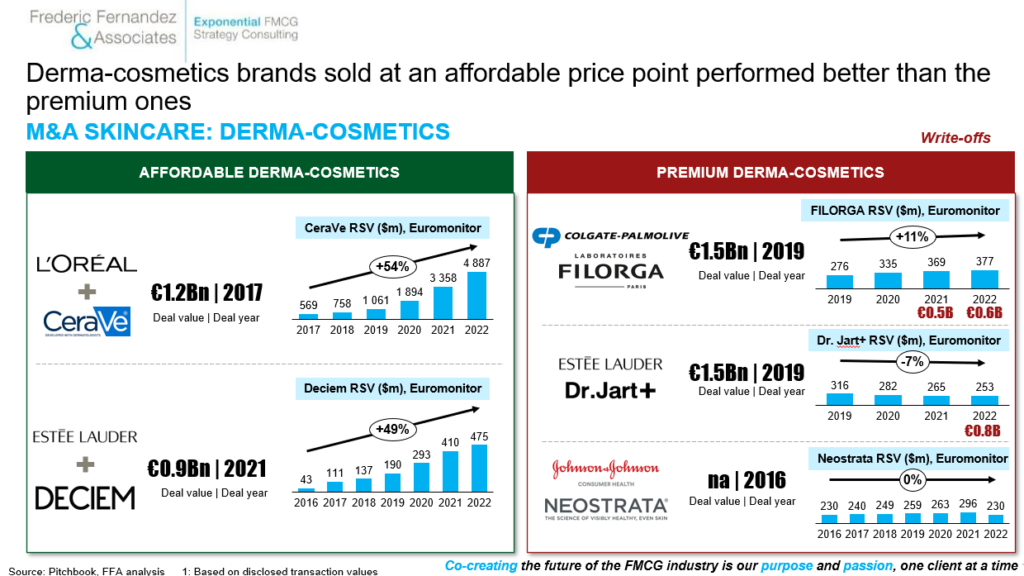

3) Out of the €49bn invested on Beauty Personal Care (BPC) acquisitions over the last decade, 12% (for now) ended up being publicly written-downs (12% of the total invested) and more will come

If those impairments are unevenly distributed (Coty, Estee Lauder, Colgate being more impacted than L’Oreal), there is a trend. Here also, we have a mixed bag of reasons that differ from one asset to another:

i) Many digital-first Color Cosmetics brands were dependent on the founders & social media to recruit consumers. Their products were insufficiently differentiated and they went through a brutal hype/ de-hype cycle

ii) Some brand growth models, like IT Cosmetics that was mostly QVC driven in the US, were not easily transferrable to a retail environment

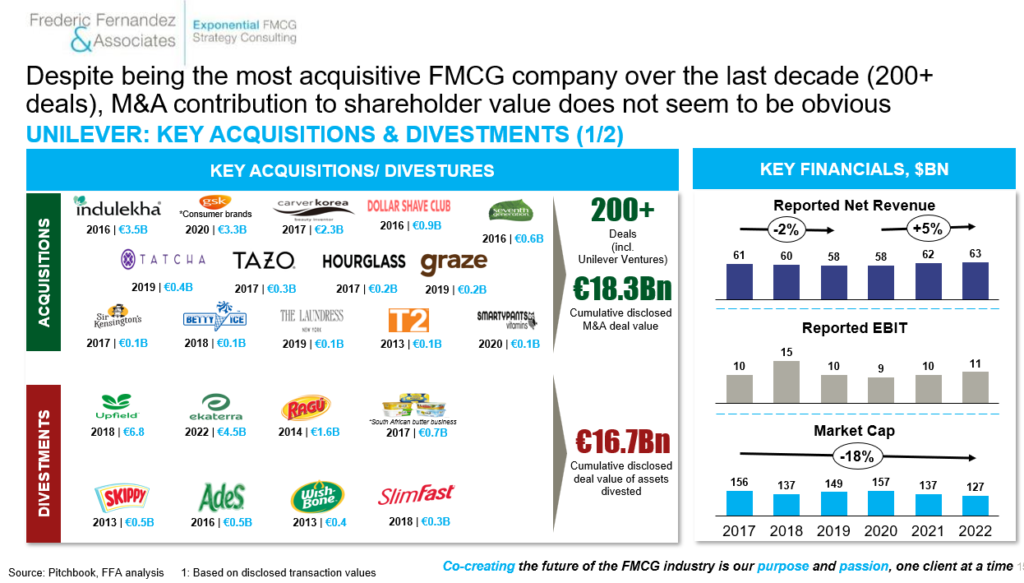

iii) Some businesses like Dollar Shave Club had an unsustainable CAC-CLTV equation with the continuous rising CPM, the emergence of online competitors (incl. Gillette), a narrowing price advantage following the price increase on their offering post Unilever acquisition and Gillette price decreases on their blades

iv) Regarding the Filorga/ Colgate deal, the size of the impairment (€1.1bn out of a €1.5bn acquisition) and the speed at which it took place (within 36 months post acquisition) suggests a large problem that may go much beyond travel retail & China COVID-induced disruption. Our hypotheses are that Filorga brand growth model may not be performing in pharmacies as well as it should (no channel exclusivity, also sold in prestige beauty channels; potentially too ‘mass’ marketing mix – TV advertising, outdoor…) and that Colgate did not have necessarily the international scale-up capabilities on the pharmacy & prestige beauty channel to accelerate dramatically Filorga growth. Only our humble hypotheses

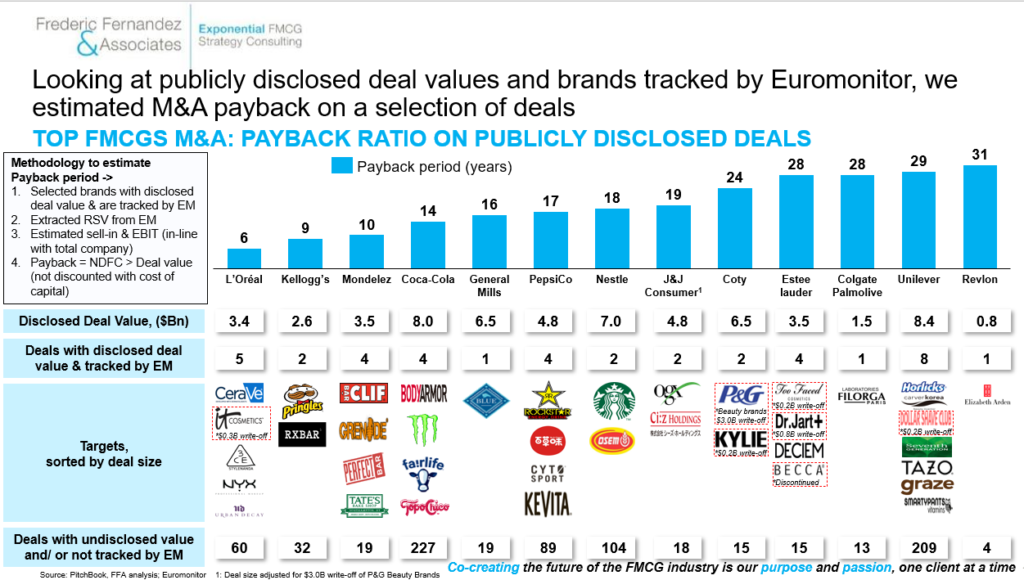

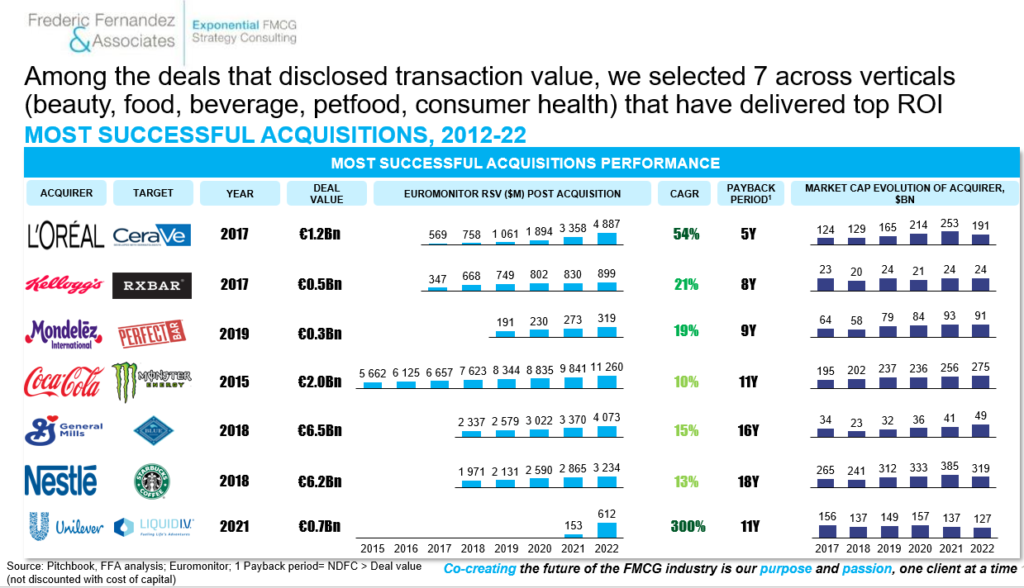

4) Our research on a small sample of deals (publicly available deal value AND brands tracked by EUROMONITOR) indicates a large standard deviation in M&A ROI performance among the world largest FMCG companies. Mid-size deals (€0.5-6bn value) outperformed. High ROI deals took place across most verticals (Household is the exception)

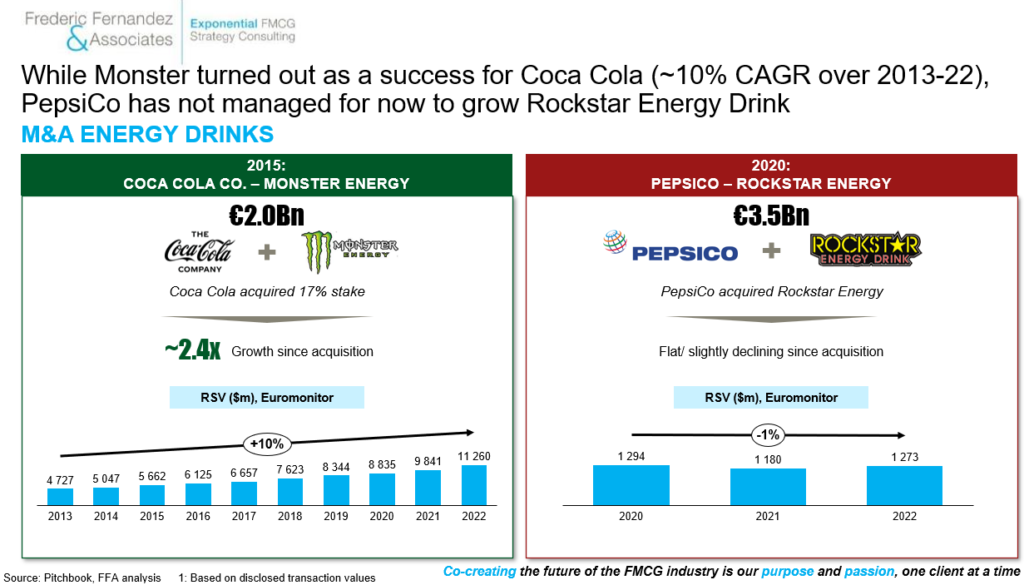

Most of those high ROI deals (CeraVe/ Starbucks/ RXBAR/ Monster) have in common four critical factors:

Beyond the above, General Mills really impressed us by its ability to get into Pet Food (which was a white space for them) with Blue Buffalo and sustain a superior growth rate. Few FMCG companies have been able to make ‘Adjacent’ moves a success

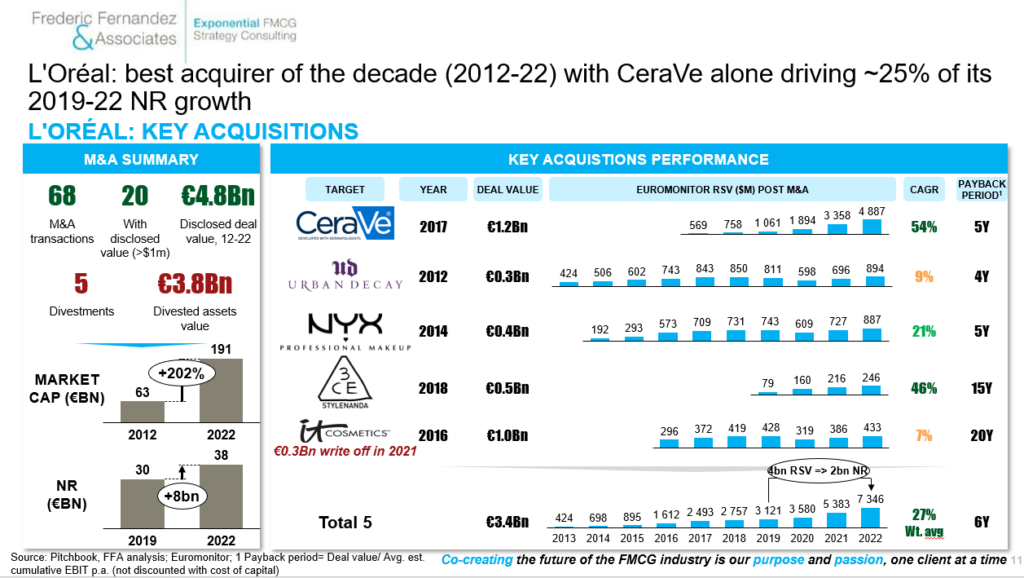

5) L’Oreal emerged as the winner of the last decade. Its star acquisition, CeraVe, drove alone 25% of its growth over 2019-22. L’Oreal continues its long tradition of successful M&A in the Beauty space. Out of its 36 international brands, only one was not acquired: L’Oreal Paris

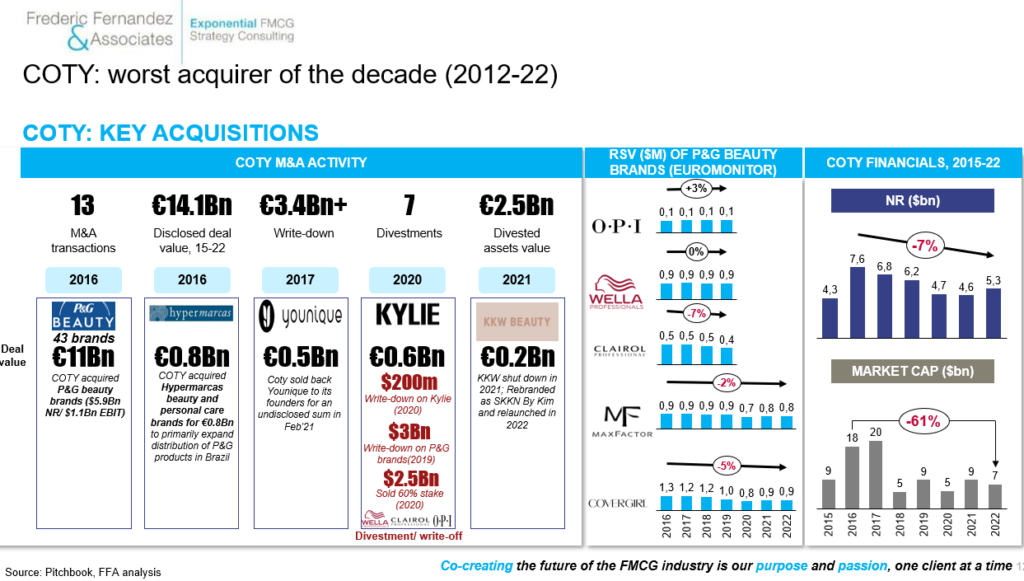

6) Coty emerged as the worst acquirer of the last decade (P&G Beauty brands, Younique, Kylie): it is the story of a $9bn market cap beauty company that spent >$15bn in M&A and that ends up being a $7bn cap in 2022 (they divested some of those assets for $2.5bn in 2020). The story is not over though as Coty has embarked into a turnaround since 2020 with the appointment of its new CEO, Sue Y. Nabi, and early results are promising

7) Skin Care M&A that focused on affordable derma-cosmetic value propositions performed best. Investments on high price-point derma-cosmetics have failed for now to deliver shareholder value, worse most recorded significant impairments (Filorga, Dr.Jart+)

8) Not all Energy Drinks transactions have, for now, delivered results

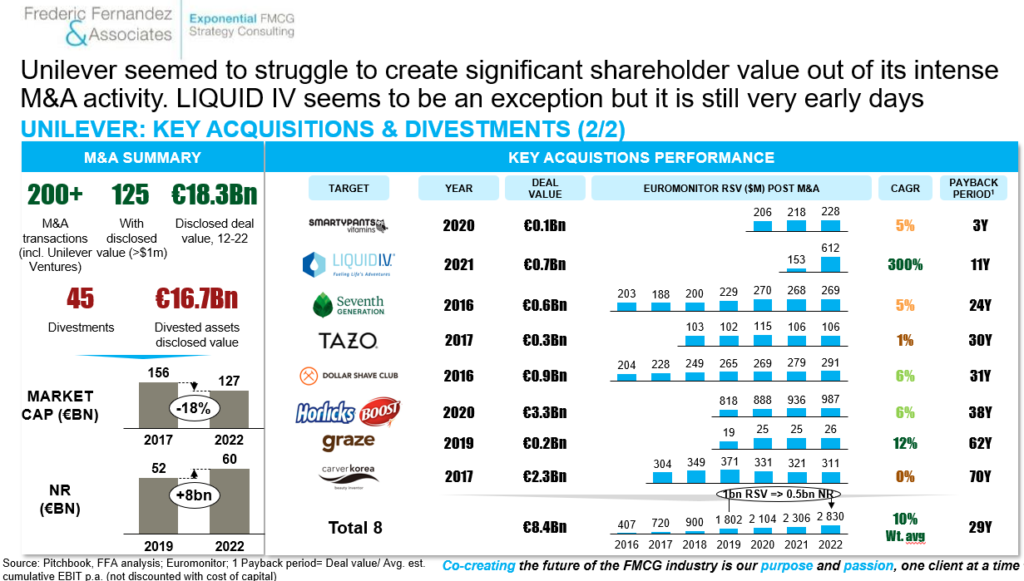

9) Unilever: despite an intense M&A/ divesture activity (especially on small deals – 75), its M&A contribution to shareholder value has not been obvious. LIQUID IV is a stand-out although it is still very early days

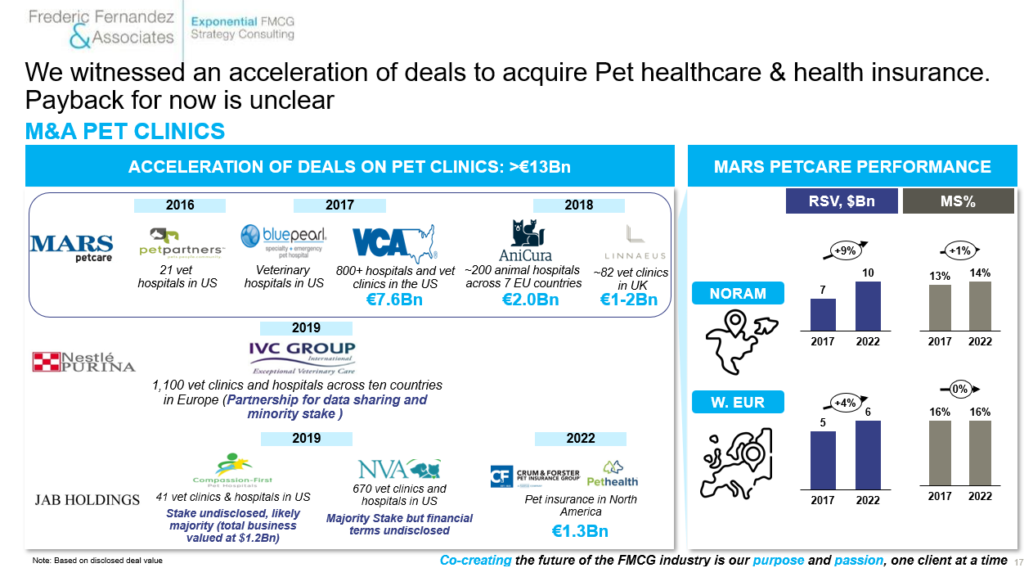

10) ROI on Pet Clinics acquisition remains for now difficult to assess. It was one of the big bet of Mars PetCare with more than €10bn invested

11) If Nestle completed a large portfolio transformation (20% rotation since 2017) through M&A/ divesture and if shareholder value creation has been top-tier over the last 5 years, those results seem to have been more driven by organic growth performance than through M&A/ divesture as contribution of the latter to organic growth has been limited (estimated at ~10% – let’s keep in mind it is a $99bn company). Like the best acquirers (including L’Oreal with IT Cosmetics), Nestle had some missteps along the way (Aimmune, Freshly) but acted decisively (in the process to put them back on sales)

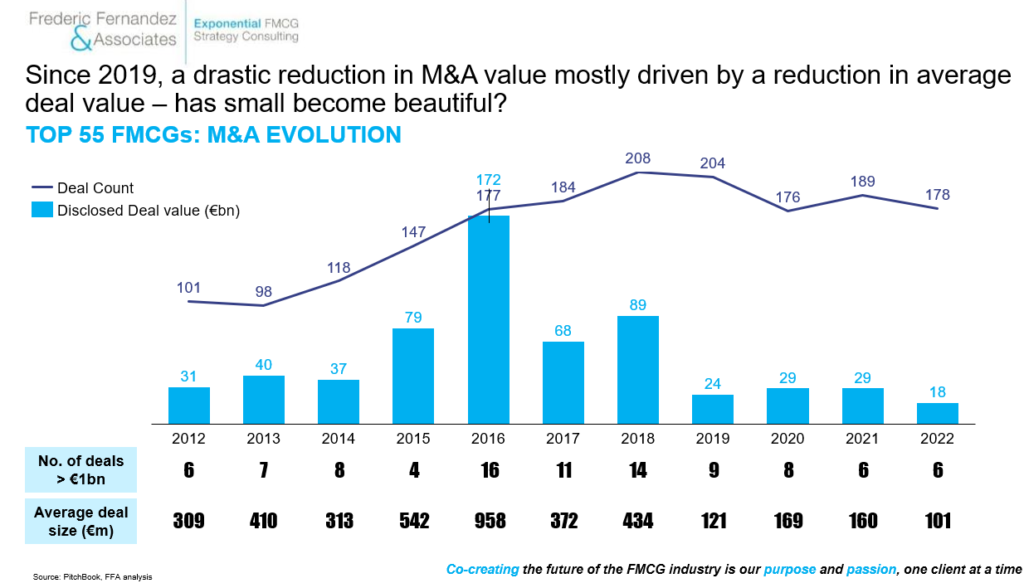

12) Looking at macro M&A trend in the FMCG industry: since 2019, we witness a drastic reduction in M&A value mostly driven by a reduction in average deal value – small has somewhat become beautiful

Few comments on the above evolution & one watch-out:

i) The 2020-22 period called for more financial prudence and saw a reduction in the execution & financial bandwidth of many companies that ended up being very busy managing multiple crisis (COVID related disruptions, Supply, Ukraine War, Inflation…)

ii) Assets prices remained elevated/ inflated vs. fundamentals and detered many acquirers

iii) Organic growth came easier for the top FMCG companies in a context challenger brands were more penalized than large brands (retailer driver SKU reduction, COGS inflation, supply chain disruption, increase in cost of capital)

iv) The world largest FMCG companies started to integrate some of their recent M&A learnings (majority of large transactions failed, many mid-size deals were written-down) and doubled-down on small acquisitions with the intent to spread risks

If small deals have a role to play in a M&A strategy, alone they tend to deliver a lower ROI than mid-sized transactions and are often not enough to move the needle.

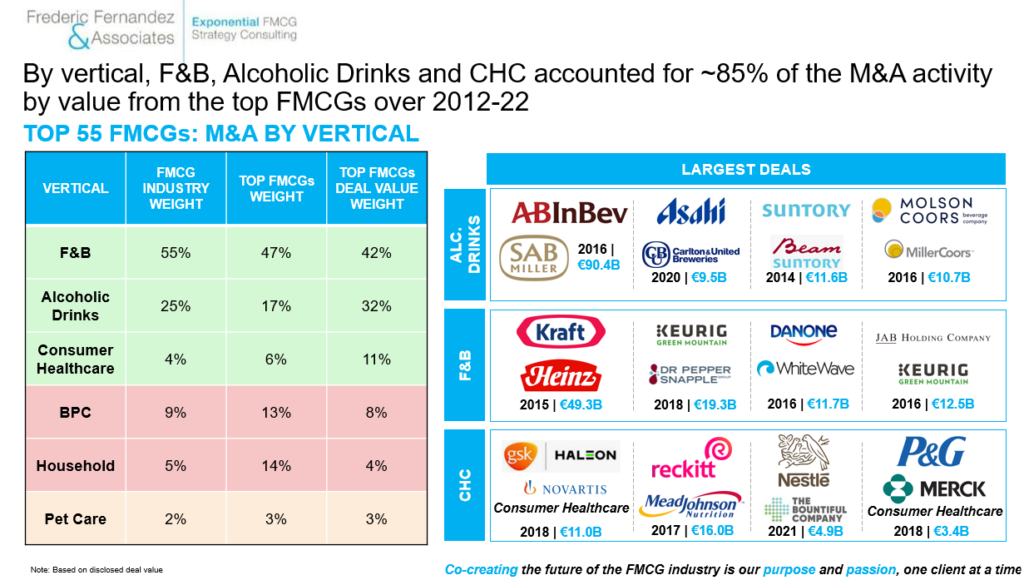

13) Food & Beverage, Alcoholic Drinks & Consumer Health verticals have been the most active verticals

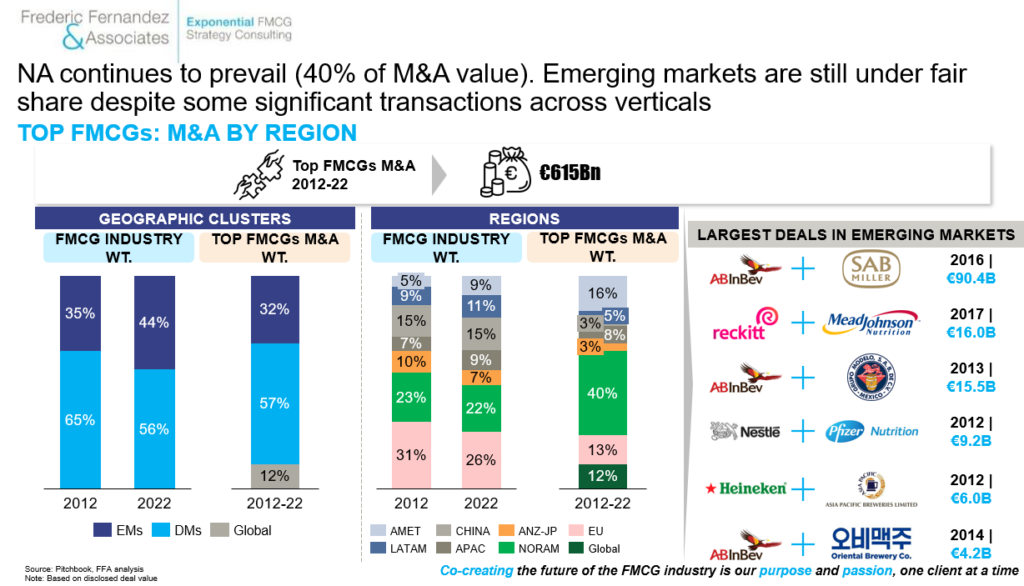

14) North America remained the favourite ground for M&A (40% of M&A deal value). Emerging Markets is the region the most under fair-share despite few major transactions mostly initiated on beer & CHC

i) NA market size provides a unique ground for local assets to scale-up

ii) NA market is seen (sometimes wrongly) as a good predictor for future global success

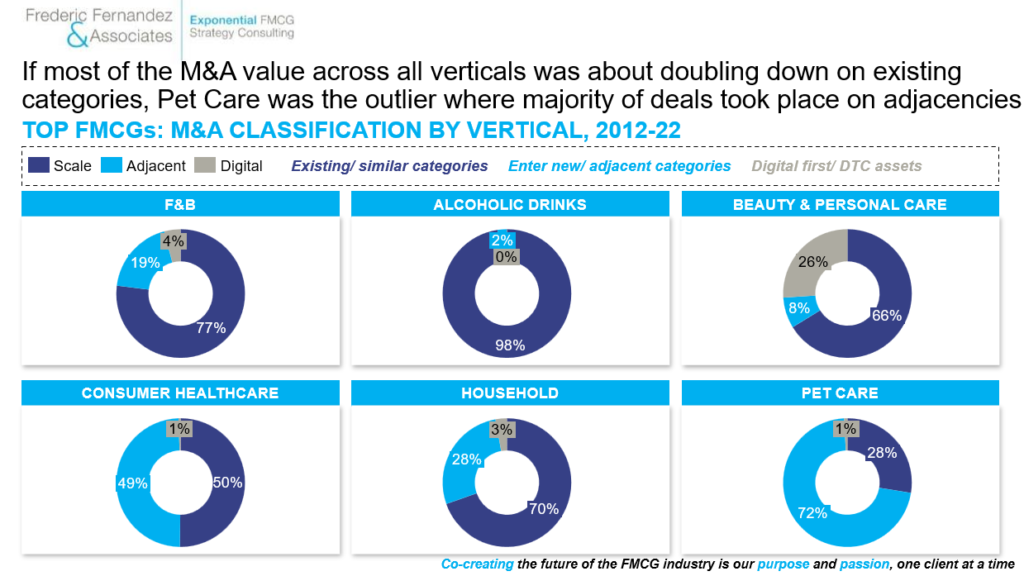

15) Most of M&A investments (77%) were directed on existing categories with the objective to leverage acquirers’ scale. The Pet Care vertical was an exception with its foray into pet clinics

PetCare was interestingly the vertical that saw the most investments going into Adjacencies (72% of M&A value) than any others, mostly because of the rush to acquire vet clinics over 2017-19

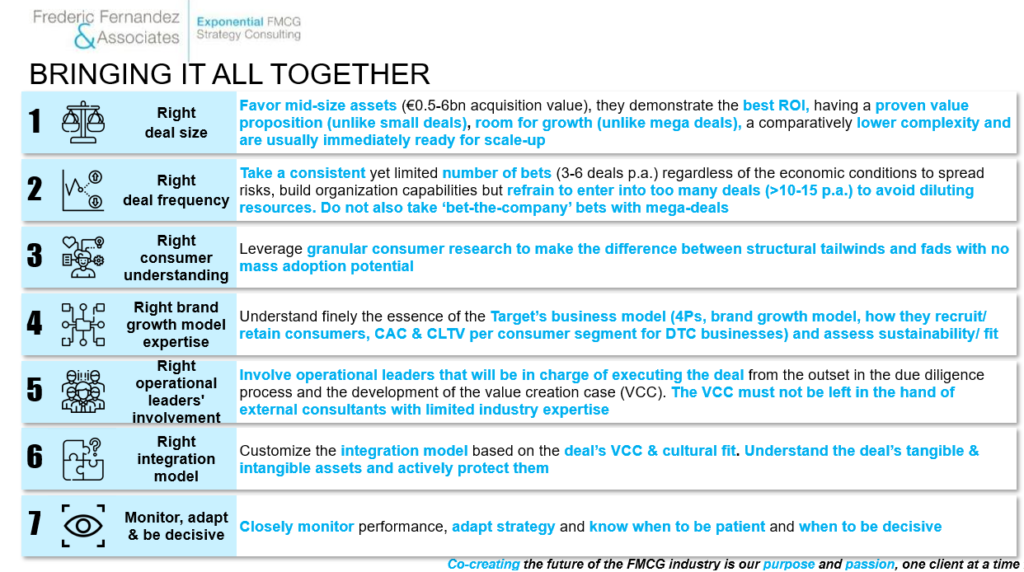

Bringing it all together & breaking the code of successful M&A in the FMCG industry – 7 key learnings emerge:

1) Size matters:

2) Frequency matters, irrespective of ‘weather’:

3) Deep consumer understanding matters & helps to make the difference between structural tailwind & fads:

4) Understanding the essence of your Target’s business model matters:

5) Involving your operational leaders in due diligences & in the elaboration of the value creation case matters:

6) Integration model matters and depends on the value creation case & the cultural fit between the two organizations:

7) Keep monitoring, learning and adapting & know when to be patient and when to be decisive:

Let’s close this article on the two opening quotes:

‘Price is what you pay. Value is what you get’

We hope the above insights will help to better understand what are the drivers between the two in the FMCG industry

‘Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful’

We hope that the high failure rate of M&A in our industry will not be a deterent to leverage the increasingly favorable context to acquire assets. At the end of the day, it is in downturn that Winners make the difference & widen the gap

Exciting & decisive times.

To get all our FMCG CEO insights, please sign-up to your bi-weekly newsletter:

#fmcg #cpg #strategy #ceoinsights #mergersacquisitionsdivestitures #growth #acquisitions #venturecapital #privateequity

To follow Frederic, please click Here, To contact him, email at: frederic@fredericfernandezassociates.com

About the author:

Frederic Fernandez is a strategic advisor in the FMCG industry. He is the Managing Director and Partner of Frederic Fernandez & Associates (FFA) a global bespoke Strategy Consulting Firm exclusively focused on the FMCG industry across all key verticals (Food & Beverage, Alcoholic Drinks, Beauty & Personal Care, Household, Consumer Health Care, PetCare, Tobacco RRP). Its purpose is to co-create the future of the FMCG industry, one client at a time. The Firm helps the CEOs and the Boards of the world’s largest FMCG companies on selected areas: Growth and Profit acceleration, New Retail/ EB2B/ Ecommerce/ DTC strategies and M&A (buy-side & sell-side). The Firm’s head office is located in Zug in Switzerland. The Firm’s team intervenes all across the globe. To know more about the Firm, please visit its website: www.fredericfernandezassociates.com

No FFA employees own any stocks or financial instruments of any FMCG companies or companies mentioned in the above article. All the above information are public information